A sharp drop in oil prices adds to rating pressures for oil-exporting Middle East and Africa (MEA) sovereigns with vulnerable public and external finances, says Fitch Ratings. A slump in tourism, weakening demand for non-oil exports, and financial volatility associated with the coronavirus epidemic could also pressure rating metrics in the region.

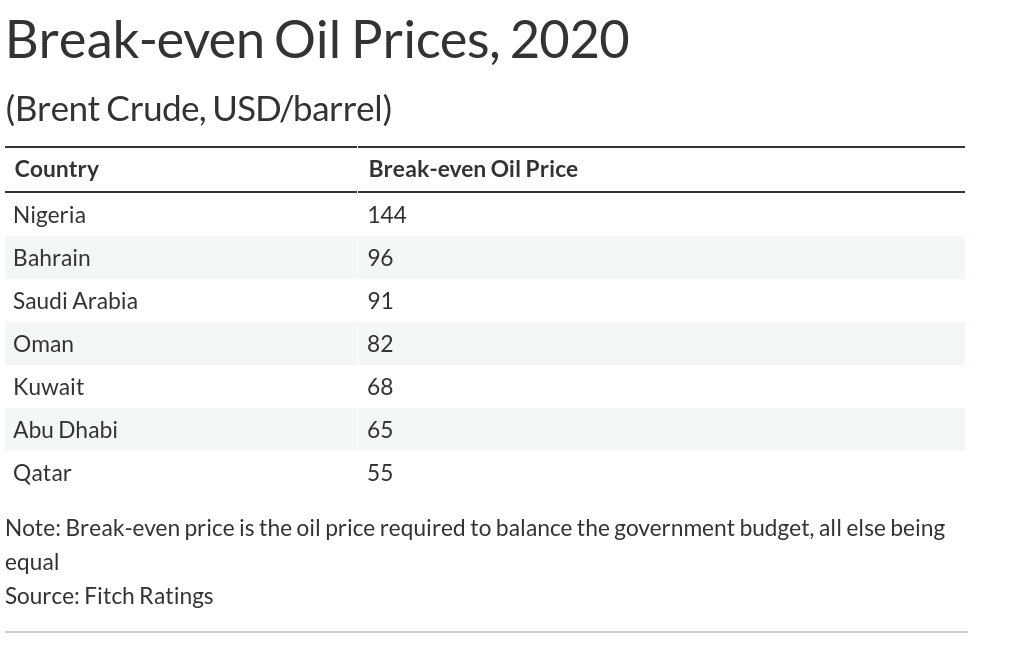

Oil prices have slumped as the impact of pandemic has grown, with the decline accelerating sharply after the collapse of OPEC+ talks on 6 March led to a shift in Saudi Arabia’s supply policy. Fiscal deficits will consequently widen in all oil producers.

For countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Fitch estimate that a change of USD10 in the price per barrel of oil tends to affect government revenues by 2%-4% of GDP. Among large African oil producers, the impact will be 1%-2% of GDP in both Angola (B-/Stable) and Gabon (B/Stable), and 0.5% in Nigeria (B+/Negative). This will add to the strain on public finances in some MEA issuers.

Angola, Bahrain (BB-/Stable), Iraq (B-/Stable), Nigeria and Oman (BB+/Stable) as well as Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) members Cameroon (B/Stable) and Gabon (B/Stable) are among the countries where weaker balance sheets and policy buffers will limit governments’ capacity to respond to the oil price slump without putting pressure on their ratings. However, a record of strong GCC support for Bahrain mitigates the liquidity risks it faces from greater funding needs.

For higher-rated oil-producing sovereigns in the GCC, such as Abu Dhabi (AA/Stable), Kuwait (AA/Stable) and Qatar (AA-/Stable), ample fiscal and external buffers will provide greater headroom to weather the shock. The drop in hydrocarbon prices will benefit oil importers in the MEA region. However, Fitch expect this will be more than offset by other adverse effects linked to the epidemic, such as a drop in external demand and lower remittances, which are sensitive to activity in GCC countries and the eurozone for most MEA sovereigns.

The drop in oil prices is not the only phenomenon associated with the coronavirus outbreak that will challenge sovereigns in the MEA region. Prices for other commodities, including metals and agricultural products, may be subdued by the demand shock associated with the disease. Any weakening in mining activity would further hinder already limited growth momentum in Namibia and South Africa. Weak growth in both countries has undermined debt trajectories and contributed to downward pressure on ratings: Namibia was downgraded to ‘BB’ from ‘BB+’ in October 2019, while South Africa’s ‘BB+’ rating remains on Negative Outlook.

In addition, global tourism flows are likely to fall sharply in 2020. This could affect Cabo Verde (B/Positive), Egypt (B+/Stable), Lebanon (C), Morocco (BBB-/Stable), Rwanda (B+/Stable), Seychelles (BB/Stable), Tunisia (B+/Negative) and Uganda (B+/Stable). The severity of the virus’ impact on travel patterns will depend on the duration of the epidemic. If disruption extends into the middle of the year, the adverse effects will increase, affecting the northern hemisphere summer season.

Souring sentiment among international investors, linked to the virus outbreak, could have significant adverse effects on financing conditions for MEA sovereigns. Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, Fitch had expected foreign-currency issuance by Middle Eastern economies to be around USD30 billion in 2020, representing both new financing and rollover of existing debts. Fitch also expected several sub-Saharan Africa sovereigns to come to market, including Angola, Cote d’Ivoire (B+/Positive) and Nigeria.

Market volatility may impede some countries from coming to market in the near term. However, the drop in benchmark yields and greater availability of official creditor funding in response to the outbreak will mitigate the tightening in funding conditions. For higher-rated GCC sovereigns, larger funding needs are likely to be covered from ample fiscal buffers and possibly larger Eurobond issuances.

U.S. Drilling Giant Diamond Offshore has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection

Diamond Offshore Drilling has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, becoming the second major victim of the oil market crash so far, after Whiting Petroleum filed earlier this month.

With a debt pile of $2.6 billion, according to the Financial Times, Diamond Drilling said the move was motivated by the unprecedented oil price crash, saying in its filing that conditions in the oil industry had “worsened precipitously in recent months.”

According to Bloomberg, at least seven oil companies in North America have gone under since the start of the year, all before WTI and other benchmarks turned negative for a day last week. This has motivated creditors to pout their demands for repayment from troubled oil players on hold to avoid ending up with assets worth pretty much nothing amid the oil demand devastation that the coronavirus pandemic wreaked on the world.

Diamond Drilling said it had tried borrowing more to stave off disaster as well as taking other steps to avoid bankruptcy but had failed. Bloomberg notes that Diamond Drilling is at a disadvantage to other drillers because it focuses on offshore drilling. Offshore drilling is a lot more expensive than onshore drilling, making the pain a lot deeper for companies focused on the former.

More bankruptcies are on the way, according to forecasters. Earlier this month, Rystad Energy warned that as many as 533 U.S. oil companies go bankrupt if oil stays at around $20 a barrel.

“$30 is already quite bad, but once you get to $20 or even $10, it’s a complete nightmare,” said Rystad’s head of shale research, Artem Abramov. He added, “At $10, almost every US E&P company that has debt will have to file Chapter 11 or consider strategic opportunities.”

Diamond Offshore has significant operations in the Gulf of Mexico.

The filing comes as the five biggest U.S. and European firms have cut spending an average of 23% in response to the drop in oil demand caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The companies are Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Total and Chevron.

Global spending on oilfield equipment and services is forecast to fall 21% this year to its lowest level since 2005. Oil futures prices last week closed below $0 for the first time in history.

Chevron, BP and others have been reducing deepwater drilling projects, including the U.S. Gulf of Mexico, where some of Diamond’s drilling rigs are located.

Loews was Diamond Offshore’s largest shareholder, with 53% as of April 3, according to Refinitiv.

Diamond had recently drawn $400 million under a revolving credit facility. But it said “the financial and operational conditions of the Diamond Offshore Group Companies have continued to deteriorate in the weeks following such responses.”

Diamond Offshore Drilling listed Bank of New York Mellon as by far its largest creditor, with a combined $2 billion in claims. The next largest creditor was National Oilwell Varco, with about $6.2 million in claims.

The company had about 2,500 workers, including international crew furnished through independent contractors, as of the end of 2019.