Maybe as some kind of Christmas gifts $1.5 Trillion In $100 Bills Have Disappeared from circulation.

Last week we reported that something strange was going on at the same time that central banks are injecting $100 billion each month in electronic money to crush volatility and ramp markets: a similar amount in physical currency and precious metals was literally disappearing.

The mystery, in a nutshell, was as follows: while banks are printing more bank notes than ever, these seem to be “disappearing off the face of the earth” and nobody knows where or why, or as the WSJ notes, “central banks don’t know where they have gone, or why, and are playing detective, trying to crack the same mystery.”

And while readers can read up much more on the topic of disappearing hard assets here, a few days after, Fox Business picked up on this thread, writing that almost $1.5 trillion of the world’s physical cash, with $100 dollar bills making up the vast majority, was reportedly unaccounted for.

So what happened to the money?

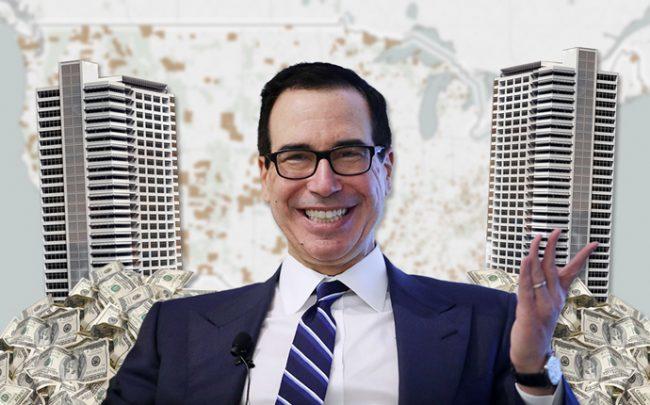

To get to the bottom of this mystery, this was the question FOX Business anchor Lou Dobbs asked the man who literally signs every single US dollar bill, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. The response” “Literally, a lot of these $100 bills are sitting in bank vaults all over the world,” Mnuchin said.

Mnuchin pointed to the negative interest rates causing people to turn to American dollars as a solid investment.

The dollar is the reserve currency of the world, and everybody wants to hold dollars,” Mnuchin said on “Lou Dobbs Tonight.” “And the reason why they want to hold dollars is because the U.S. is a safe place to have your money, to invest and to hold your assets.”

Mnuchin said it’s interesting that, in a increasingly digital world, “the demand for U.S. currency continues to go up.” adding that “there’s a lot of Benjamins all over the world.”

Actually, it’s not that interesting: the world’s growing appetite for physical assets such as paper dollars and gold, coupled with the continued interest in cryptocurrencies and other traditional currency alternatives, merely confirms that faith in artificially levitated markets is approaching a tipping point. Meanwhile the world’s “top 0.001%ers” continue to quietly cash out, literally, and put their Benjamins in secret vaults in the middle of somewhere, even as central banks do everything in their power to reduce the amount of physical currency in circulation and replace it with easily trackable digital alternatives.

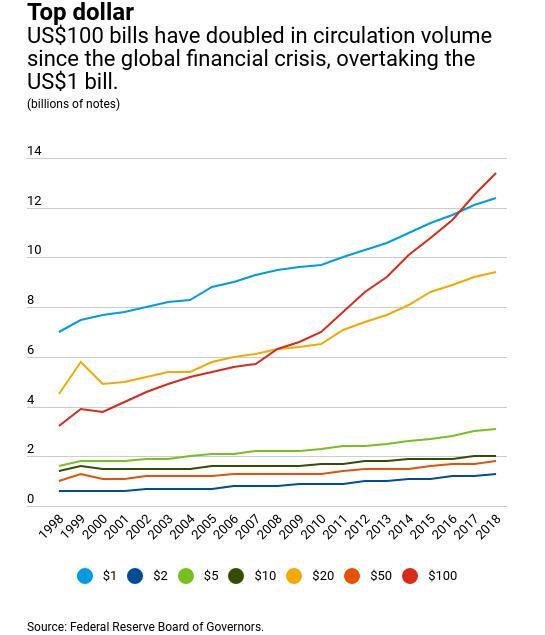

As we reported back in August, there are now more $100 bills in circulation than $1 bills, according to data from the Federal Reserve, which found there are more $100s than any other denomination of U.S. currency. And as an indication of just how much demand there is for physical stores of value, consider this: the number of bills featuring a picture of Benjamin Franklin has about doubled since the start of the recession.

In 2018, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago illustrated a correlation between low interest rates and high currency demand, though it also noted outside factors could help explain swelling demand.

The bank estimated that 80% of all $100 bills last year were actually in circulation in foreign countries, and explained that residents in other countries, particularly those with unstable financial systems, often use the notes as a safe haven.

It’s not just US dollar that are disappearing, however.

Few are as perplexed by the fate of the missing cash as the German central bank: according to the Bundesbank more than 150 billion euros are being hoarded in Germany. This has led the European Central Bank, and others, to ask the public for help.

“Everyone says that they are not hoarding cash but the money is clearly somewhere,” said Henk Esselink, head of the issue and circulation section in the ECB’s currency management division.

“People hide their money everywhere,” said Sven Bertelmann, head of the Bundesbank’s National Analysis Centre in Mainz, Germany. Sometimes bank notes are buried in the garden, where they start decomposing, or hidden in attics, where they are used by mice for building nests. “It happens again and again that people keep money in an envelope and then they shred it by mistake,” Bertelmann said. “We pick up the bank notes with tweezers and then start to put them together, like a jigsaw puzzle.”

Australia’s central bank says its best guess is that only around a quarter of the bank notes in circulation are used for everyday transactions. Up to 8% of cash is used in the shadow economy—tax avoidance or illegal payments—while as much as 10% could have been lost. That is $7.6 billion Australian dollars ($5.2 billion) missing at the beach or in couch cushions… Or simply lost in a “boating accident” to avoid the taxman until the rainy days arrive.

The biggest use of cash is as a store of wealth “in safes, under beds and at the back of cupboards, both here in Australia and elsewhere around the world,” Mr. Lowe, the RBA governor, said.

Swiss National Bank officials likewise found that hoarding of Swiss francs jumped around the year 2000, likely motivated by fear of the Y2K bug infecting computer systems, the bursting of the dot-com bubble, the September 11 terrorist attacks and introduction of the euro. The financial crisis that began in 2007 encouraged people to stash even more.

Meanwhile, with a financial crisis looming – and getting closer by the day – for some countries, such as New Zealand, making money disappear is becoming a national pastime. Around a third of New Zealand’s new bank notes headed overseas in 2017, up from 6% four years earlier. That happened around the time that tourism overtook dairy as the country’s main export money-spinner, leading officials to speculate on the role played by currency exchanges, especially in Asia.

The trail mostly ran cold after that. The bank could only identify the whereabouts of around 25% of New Zealand’s cash. The rest, of about 75%, has disappeared.

“Our sense is that we’re in the same boat as a lot of other central banks out there,” said Christian Hawkesby, assistant governor at the RBNZ. “We can’t fully explain why holdings of cash are rising and where they are going.”